What is beauty for? If you assume that art and beauty are somehow allied you can ask this in another way: Why is there art? On the surface, these questions seem quite different. Examine them closely and you will see that they are, at the heart, the same.

In matters of personal growth, we live in an oddly pragmatic time. The Gilded Age that closed the 19th century was as rapacious as our own, yet a college education was valued then because it enhanced the men who achieved one. Art was valued because it reflected and defined our better natures and bound us together as a culture. After taking a liberal arts degree and gaining a familiarity with the Latin and Greek classics, a well-heeled young man made a grand tour of Europe, where he would sample great art and the ruins of the classic civilizations. He returned a cultured man of the world.

In matters of personal growth, we live in an oddly pragmatic time. The Gilded Age that closed the 19th century was as rapacious as our own, yet a college education was valued then because it enhanced the men who achieved one. Art was valued because it reflected and defined our better natures and bound us together as a culture. After taking a liberal arts degree and gaining a familiarity with the Latin and Greek classics, a well-heeled young man made a grand tour of Europe, where he would sample great art and the ruins of the classic civilizations. He returned a cultured man of the world.

***

(To be clear, by culture I do not mean popular culture. This is about fashion and celebrity, which are ephemeral. The influences of Jenny Lind or the Kim Kardashian may be widespread in their times, but they are exceedingly fleeting. By culture, I mean the lasting foundations that shape our ideas about ourselves. In the Gilded Age that meant European art, history, and science, and a flirtation with ancient Egypt. Today many of us would include contributions of the Far East, the Near East, and the Americas. This broadening of world-view has not come without frictions, and has not been fully achieved by any means.

I also need to distinguish between art and art collecting. Like most collectors, art collectors buy with a thought to investment, which is a measureable parameter, though it does not say much about the art itself. Since any given artist’s production is limited, and becomes fixed on the artist’s death, the law of supply and demand suggests that a popular artist’s work may grow extremely costly. The fact that Mark Rothko’s Painting No. 6 (Violet, Green, and Red) sold for €140 million ($186 million) relied on a number of factors, among the least of which was its artistic merit. The art to which I am referring is an unmeasurable (and practically indescribable) quality, which connects that mysterious creative place in the artist’s soul to that equally mysterious receptor within the appreciator of art. This has to be experienced to be understood. It is where art resides.

I also need to distinguish between art and art collecting. Like most collectors, art collectors buy with a thought to investment, which is a measureable parameter, though it does not say much about the art itself. Since any given artist’s production is limited, and becomes fixed on the artist’s death, the law of supply and demand suggests that a popular artist’s work may grow extremely costly. The fact that Mark Rothko’s Painting No. 6 (Violet, Green, and Red) sold for €140 million ($186 million) relied on a number of factors, among the least of which was its artistic merit. The art to which I am referring is an unmeasurable (and practically indescribable) quality, which connects that mysterious creative place in the artist’s soul to that equally mysterious receptor within the appreciator of art. This has to be experienced to be understood. It is where art resides.

Today the world demands “value”, not culture, in return for the cost, time, and effort it takes to achieve a college degree. We now define value in terms of the ability to attract or generate money. The liberal arts, art for art’s sake, are dying. The voices of Heraclitus and Marcus Aurelius have fallen silent. In their place have risen studies that have a payoff at the end: science, engineering, finance. The grand tour is undertaken, if at all, as a business trip.

Today the world demands “value”, not culture, in return for the cost, time, and effort it takes to achieve a college degree. We now define value in terms of the ability to attract or generate money. The liberal arts, art for art’s sake, are dying. The voices of Heraclitus and Marcus Aurelius have fallen silent. In their place have risen studies that have a payoff at the end: science, engineering, finance. The grand tour is undertaken, if at all, as a business trip.

An attractive feature of this way of thinking is that it is measurable in a way that personal and cultural enrichment are not. Measurement is highly prized in our over-managed, computerized society. I have seen lists, published as aids for high schoolers as they choose a college, which rank institutions of higher learning in order of the salaries commanded by alumni in the first year after they graduate. To rank them by, say, the satisfaction with their lives enjoyed by those first-year graduates, or their degree of well-rounded participation in our culture as opposed to our economy, would be far more difficult to enumerate.)

***

Chauvet cave painting

Art has been a part of human activity since the first humans walked the earth. From the beginning, art has been closely allied to the sacred. There is apparently reason to believe that the ancient caves that harbor paintings, like those at Altamira or Chauvet, were sacred places, and that the paintings themselves, almost exclusively of hunting prey, held magical powers that would enhance the success of the hunt and the prosperity of the clan. The live-stenciled outline of an upraised hand, produced by blowing pigment through a reed at a hand pressed against the cave wall, was magical as well, perhaps transforming a young boy into a hunter. The ritual bound a tribe together, creating a fellowship that survived even death, and continues to do so even after thirty thousand years.

“Adam and Eve” Etching Rembrandt 1638

By the Italian renaissance, the church had enormous influence and inspiration to painting, sculpture and music, as the works in the Sistine Chapel and the surviving Gregorian chants bear witness. Today fine art painting has largely moved on from religious motifs, but kitsch art, like porcelain saints and portraits of a praying Jesus painted on black velvet, continue to sell well. Serious religious sculpture and gospel music are going strong.

I do not believe that the closeness of the religion and art is an accident. To experience the sacred is not unlike experiencing beauty. Both provoke within us a sense of comfort, and of a connection to something benevolent that is greater than we are. To varying degrees, they both inspire awe. That may be reason enough for art to be.

Is the impulse to make art, the quest for beauty, the result of cultural conditioning, or is it something intrinsic to being human? Denis Dutton, the outspoken philosopher of art, argues in his book The Art Instinct that the ability to perceive beauty is a hereditary trait that evolved as arboreal hominids descended from the trees to walk upright in the grasslands below. Here he summarizes the idea in his TED Talk, A Darwinian Theory of Beauty:

Savanna in modern Tanzania

“Consider briefly an important source of aesthetic pleasure, the magnetic pull of beautiful landscapes. People in very different cultures all over the world tend to like a particular kind of landscape, a landscape that just happens to be similar to the pleistocene savannas where we evolved. This landscape shows up today on calendars, on postcards, in the design of golf courses and public parks and in gold-framed pictures that hang in living rooms from New York to New Zealand. It’s a kind of Hudson River school landscape featuring open spaces of low grasses interspersed with copses of trees. The trees, by the way, are often preferred if they fork near the ground, that is to say, if they’re trees you could scramble up if you were in a tight fix. The landscape shows the presence of water directly in view, or evidence of water in a bluish distance, indications of animal or bird life as well as diverse greenery and finally — get this — a path or a road, perhaps a riverbank or a shoreline, that extends into the distance, almost inviting you to follow it. This landscape type is regarded as beautiful, even by people in countries that don’t have it. The ideal savanna landscape is one of the clearest examples where human beings everywhere find beauty in similar visual experience.”

To be drawn to such a landscape would confer a survival advantage to early pleistocene man, for it was rich in the resources that he needed to thrive. That we feel it today as we contemplate a Corot or Constable is a gift.

The art instinct is also conditioned by our expectations and the social context of the piece. Yale Psychologist Paul Bloom, in his TED Talk entitled The Origins of Pleasure, tells an anecdote that illustrates this. (It is rather lengthy, but you don’t have to read it. Link to the talk and listen to the whole thing; it is well worth it if you care about beauty and the quirks of the human mind.)

“I’m going to talk today about the pleasures of everyday life. But I want to begin with a story of an unusual and terrible man. This is Hermann Goering. Goering was Hitler’s second in command in World War II, his designated successor. And like Hitler, Goering fancied himself a collector of art. He went through Europe, through World War II, stealing, extorting and occasionally buying various paintings for his collection. And what he really wanted was something by Vermeer. Hitler had two of them, and he didn’t have any. So he finally found an art dealer, a Dutch art dealer named Han van Meegeren, who sold him a wonderful Vermeer for the cost of what would now be 10 million dollars. And it was his favorite artwork ever.

World War II came to an end, and Goering was captured, tried at Nuremberg and ultimately sentenced to death. Then the Allied forces went through his collections and found the paintings and went after the people who sold it to him. And at some point the Dutch police came into Amsterdam and arrested Van Meegeren. Van Meegeren was charged with the crime of treason, which is itself punishable by death. Six weeks into his prison sentence, van Meegeren confessed. But he didn’t confess to treason. He said, “I did not sell a great masterpiece to that Nazi. I painted it myself; I’m a forger.” Now nobody believed him. And he said, “I’ll prove it. Bring me a canvas and some paint, and I will paint a Vermeer much better than I sold that disgusting Nazi. I also need alcohol and morphine, because it’s the only way I can work.” (Laughter) So they brought him in. He painted a beautiful Vermeer. And then the charges of treason were dropped. He had a lesser charge of forgery, got a year sentence and died a hero to the Dutch people. There’s a lot more to be said about van Meegeren, but I want to turn now to Goering, who’s pictured here being interrogated at Nuremberg.

Now Goering was, by all accounts, a terrible man. Even for a Nazi, he was a terrible man. His American interrogators described him as an amicable psychopath. But you could feel sympathy for the reaction he had when he was told that his favorite painting was actually a forgery. According to his biographer, “He looked as if for the first time he had discovered there was evil in the world.” And he killed himself soon afterwards. He had discovered after all that the painting he thought was this was actually that. It looked the same, but it had a different origin, it was a different artwork.

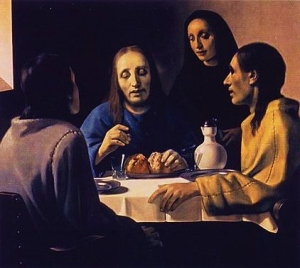

Supper at Emmaus

It wasn’t just he who was in for a shock. Once van Meegeren was on trial, he couldn’t stop talking. And he boasted about all the great masterpieces that he himself had painted that were attributed to other artists. In particular, “The Supper at Emmaus” which was viewed as Vermeer’s finest masterpiece, his best work — people would come [from] all over the world to see it — was actually a forgery. It was not that painting, but this painting. And when that was discovered, it lost all its value and was taken away from the museum.

Humans are, to some extent, natural born essentialists. What I mean by this is we don’t just respond to things as we see them, or feel them, or hear them. Rather, our response is conditioned on our beliefs, about what they really are, what they came from, what they’re made of, what their hidden nature is. I want to suggest that this is true, not just for how we think about things, but how we react to things.”

In the same TED Talk Bloom points out that the way we perceive the beauty of other people depends, among other things, on whether or not we like them:

In the same TED Talk Bloom points out that the way we perceive the beauty of other people depends, among other things, on whether or not we like them:

“Maybe one of the most heartening findings from the psychology of pleasure is there’s more to looking good than your physical appearance.” He points out. “If you like somebody, they look better to you. This is why spouses in happy marriages tend to think that their husband or wife looks much better than anyone else thinks that they do.”

This ability, to distinguish between the real and a sham, also had survival value in the Pleistocene era, when the exchange of objects between people or tribes could seal an empowering alliance, or represent fatal treachery. The perception of beauty, conditioned by social factors, may have played a role in the extension of the prolonged rearing period that characterized human development as it evolved in the Pleistocene era.

It is possible that the perception of beauty evolved when arboreal hominids descended from the trees enroute to becoming humans. At the same time the ability to entertain complex symbolic thought was bubbling up in the surging hominin brain, enabling language as well as representative drawing and sculpture. It was a perfect storm: symbolic thinking and the appreciation of beauty arising together in the awakening human mind. That art should arise in this environment seems inevitable to me. That it should be the bailiwick of shamans and priests, keepers of the ancient mysteries and dealers in symbolism, seems just as natural to me.

Today the value of beauty for the survival of the species is less clear. We no longer need the inner pleasure of overlooking a bountiful landscape to find a safe abode. That pleasure for the individual is still there, though, and it is a gift. Ars gratia artis: art for art’s sake. That’s good enough for me.

(Aside: That phrase–ars gratia artis—is often attributed to an anonymous poet in ancient Rome. It fact, it was probably coined by the 19th century poet and critic, Thèophile Gautier, in French: l’art grâce à l’art. How it found its way into Latin is neither known nor surprising; in those days Latin was the common language of the genteel in Europe.

You must be logged in to post a comment.